Before the 501(c)3, There Was the Community

Black History Month tends to give us individuals. What it leaves out is the systems.

The infrastructure. The mutual aid societies, the collective economies, the self-organized networks that Black communities built not because they had extra resources, but because they understood, long before the nonprofit sector existed, that survival is collective.

That story runs right through Los Angeles.

Black Mexican communities have been part of the Los Angeles region for centuries, shaping civic, cultural, and economic life during the city’s early formation under Spanish and Mexican rule. Historical records show that many of the early residents documented in 1781 were of African or mixed African ancestry, reflecting the longstanding presence of Afro-Mexican families across Alta California.

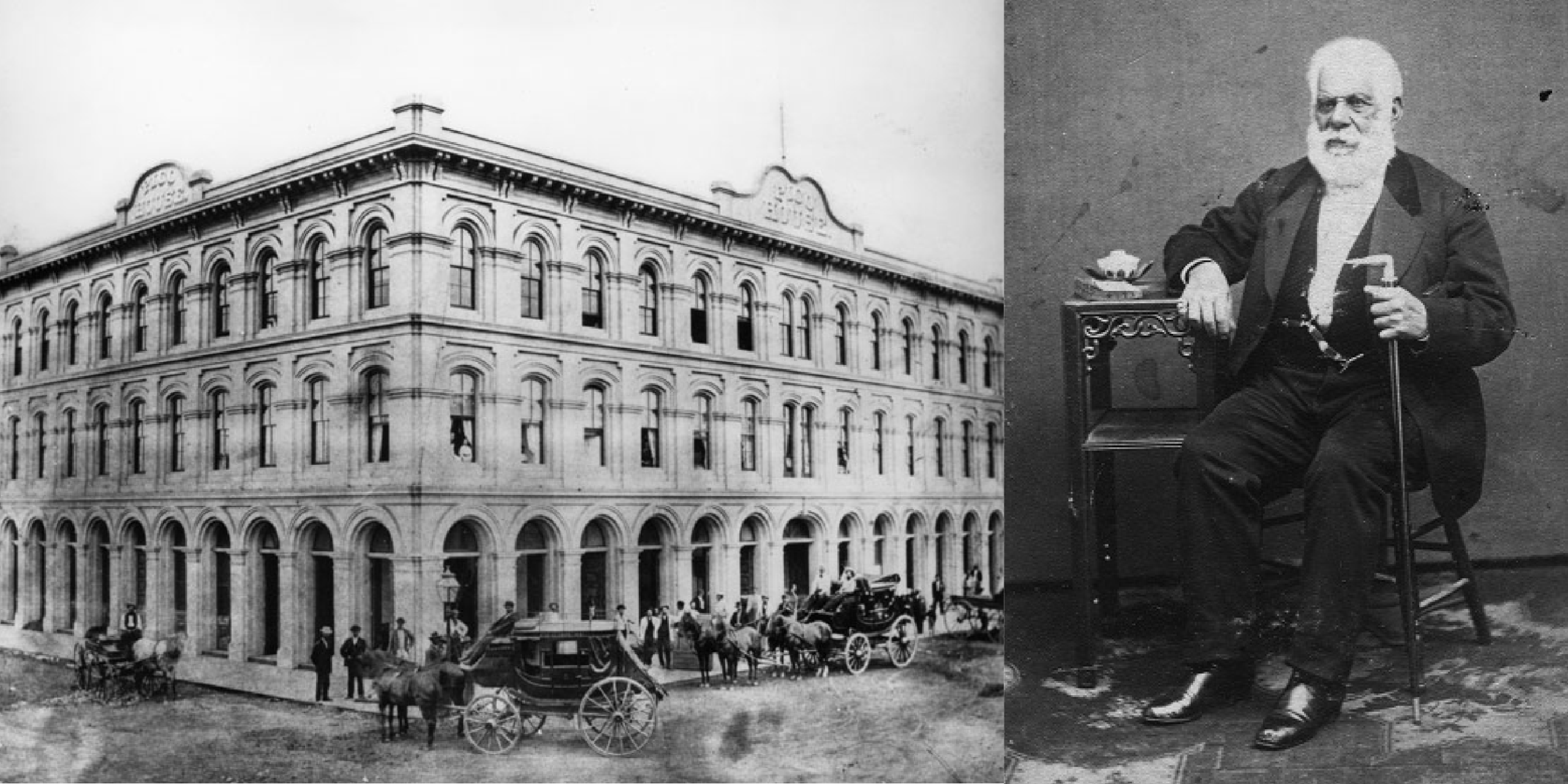

Leaders such as Juana Briones, a prominent businesswoman and landowner; Pío Pico, the last governor of Mexican California; and Tiburcio Tapia, a soldier, judge, and three-term mayor of Los Angeles, illustrate the breadth of Afro-Mexican leadership in the region. Their names remain preserved in archival records and public markers, though changes in racial classification over time reveal how some families navigated shifting systems of power by strategically reidentifying, at times obscuring their African heritage, to remain rooted in the region. The history of Los Angeles is therefore inseparable from the enduring presence of Afro-Mexican communities, whose contributions have shaped the city, and from the continuing stewardship of Indigenous peoples, whose lands these histories share.

At the same moment that Black communities in the West were building civic and economic life under shifting colonial systems, Black communities in the East were building formal mutual-aid institutions that would later serve as models for the modern nonprofit sector.

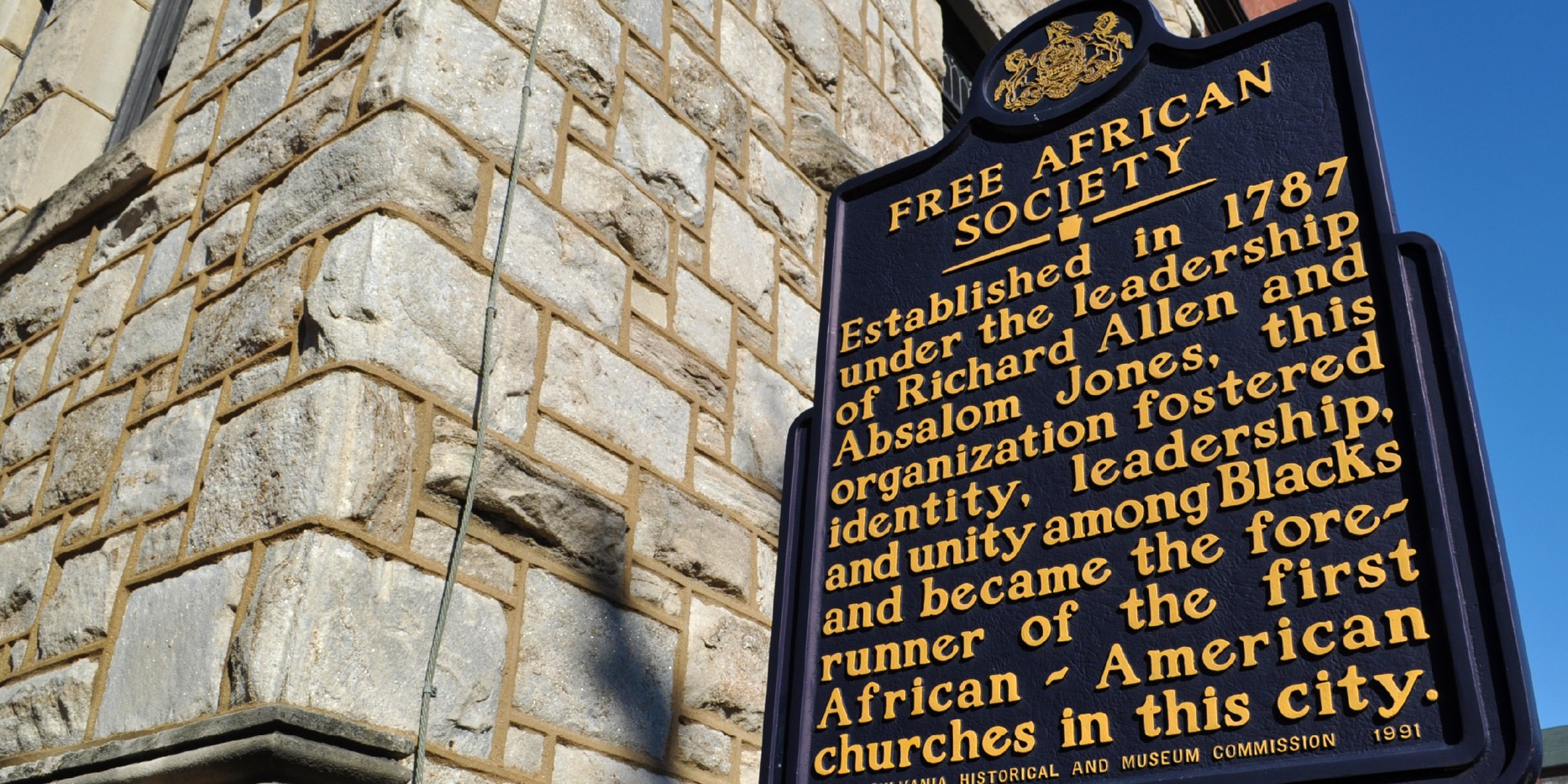

In 1787 in Philadelphia, Richard Allen and Absalom Jones walked out of a church where Black members were forced to sit in the gallery and built a new one. The Free African Society they founded was, by any modern definition, a nonprofit, supporting widows and orphans, funding education, providing burial services, and offering financial guidance that would become a model for Black banking systems. Built from scratch, with no philanthropic backing, on the understanding that when the state will not protect you, you protect each other. It spread to Boston, New York, and Rhode Island. Not because it was well-marketed. Because the need was universal and the model worked.

These weren’t isolated acts of charity. Mutual aid and collective economies were longstanding traditions that Black communities carried through enslavement, through Reconstruction, through the Great Migration — sustained because they were necessary for survival. Today, Black households give 25% more of their income annually than white households, totaling $11 billion a year. This is not despite hardship. It is because of a long tradition of understanding that the community is the safety net.

The nonprofit sector runs on structures that Black communities developed out of necessity and sustained through ingenuity. When discussing the history of this work, we should be clear about its origins.

Not just the exceptional individuals. The systems.

Black History Month is almost over. The history isn’t.